Why So Many South Asian Men Are Mama’s Boys The epidemic even has a name: Raja Beta Syndrome.

- SADAF AHSAN

- Aug 28, 2023

- 8 min read

SADAF AHSAN

July 12, 2023

In the third season of the Netflix sitcom Never Have I Ever, thirsty high-schooler Devi Vishwakumar (Maitreyi Ramakrishnan) finally gets herself a mom-approved Indian boyfriend, Des (Anirudh Pisharody). But things take a turn after his mother, Rhyah (Sarayu Blue), comforts Devi through a painful memory of her father. She later tells Des, “That girl has a lot of problems,” pushing him to end the relationship.

Des cancels plans with Devi and grows cold. When Devi finally confronts him, he explains, “Look, Devi, you’re cool and all, but, like, dating you isn’t worth pissing off my mom. I mean, she still pays for my phone.”

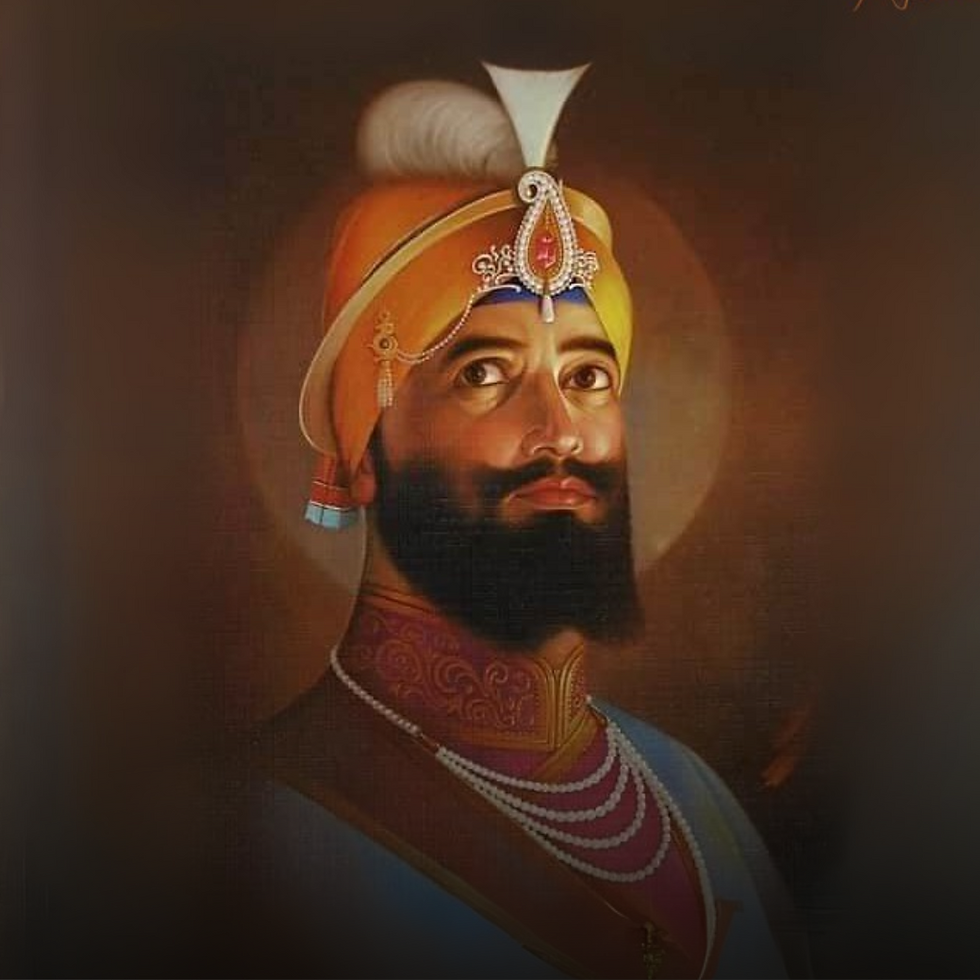

Deservedly, Devi then throws a cup of (iced!) coffee into Des’s face, and the two call it quits. It’s a maddening narrative, but one familiar to many women. Not just those who have dated men like this, but who are the daughters, sisters, and cousins of men like this. Nay, boys like this. In the West, this cringe-inducing demographic is called “mama’s boys,” and in parts of South Asia “raja betas.” This dynamic has reigned long and hard in subcontinental cultures — with far longer-lasting consequences.

In ancient times, gender roles were less rigid in South Asia than they are today. Research suggests women shared equal status with men in the Vedic era, and had more opportunities. In 1500 B.C., with the cementing of the caste system, women lost their status, and patriarchy gained a foothold. The Mughal era and British colonialism only exacerbated this.

“A woman’s place in her marital home remained precarious, unless she gave birth to a son,” said Anshu Malhotra, a professor of global studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “A woman with many sons was considered fortunate, and one with many daughters unfortunate. These biases still prevail in society, [and] societies carry their biases and attitudes as they move into the diaspora.”

This preference toward sons is hard to ignore, particularly in Pakistan and India, where sex ratios are skewed. India has one of the world’s highest rates of female infanticide, and has seen an uptick in sex-selective abortion. Studies have also found that, in South Asian societies, daughters are less likely to be born, live past childhood, go to school, receive medical treatment, and live above subsistence compared to sons.

“A woman’s place in her marital home remained precarious, unless she gave birth to a son.”

— Anshu Malhotra

In a 1982 report, sociologist Roger Ballard, who studied South Asian communities in the U.K., wrote, “Only sons had full rights of inheritance and so remained family members all their lives. At marriage, daughters left their natal home and became members of their husbands’ family… Long-term stability was most crucially guaranteed by the birth of sons, whose eventual marriage would sustain the group for a further generation.”

As the cycle continues, this practice has consequences.

“It’s not that mothers love their sons more. It’s that this is a deep and historically-rooted, structural issue,” said Prerna Singh, a political science professor at Brown University. “You just have to look at the most basic indicators of women’s wellbeing to realize that India is one of the worst places in the world to be a woman, if you’re lucky enough to be born in the first place.”

My mother, who loves me and my sister greatly, has an undeniable bond with my brother (who also happens to be the youngest child, as if he needed more brownie points). She often laments the day he will marry, who he will marry, only to “leave her behind,” loveless and lonely. For the record, my father is very much alive. Still, their marriage was an arrangement, and although they are best friends, my mother faced many trials — including a tough-as-nails, son-loving mother-in-law — leaving her family to join his. Like many South Asian mothers, my brother represents all her hard work and sacrifice: he is smart, successful, and handsome, and therefore, an eligible bachelor. In another way, she is living the life she could not through him.

“The tragic thing is…these mothers are in really precarious and vulnerable positions within the family. They are very rarely the big decision-makers,” said Singh. “Growing up, they probably received less nutrition, less education, less attention, based on broad demographic indicators…In many instances within the household, they are also the victims of domestic violence on the part of their husbands and/or fathers.”

According to a 2021 survey of 468 South Asians across the U.S., 48% experienced physical violence, 38% emotional violence, 35% economic violence, 27% verbal violence, 19% in-laws-based violence, and 11% sexual violence. The survey also notes that South Asian culture tends to “disempower” women from “recognizing and reporting” abuse, meaning numbers could be significantly higher.

“The tragic thing is…these mothers are in really precarious and vulnerable positions within the family.”

— Prerna Singh

In a 2023 report, non-profit Laadliyan spoke with 16 South Asian daughters about their experiences with gender-based violence. They expressed feeling shame, helplessness, and guilt, while also feeling resentment toward their parents, particularly their mothers.

These sons’ partners also face the consequences of mother-son dynamics. They become second mothers, cooking and cleaning for their husbands, while their mothers-in-law perceive them as a threat. This pattern continues through generations. According to a 1998 report, “The role of women is based upon a hierarchy of power and respect, with the paternal grandmother having the utmost power in the upbringing of her son’s children…South Asian women are respected if they give birth to sons. By giving birth to sons, they too will one day, as mothers-in-law, achieve a higher status in South Asian communities.”

One woman shared with me that she feels like “the third wheel” in her marriage, where her mother-in-law’s opinion is the ultimate one, and she’s often reminded her that her son “could’ve done better.” While she acknowledges that her mother-in-law seems to be projecting her struggles onto her, she and her husband live separately due to the tension.

“There have been times where I’ve said something to my boyfriend and it’s paid no heed, but when his mother says the same, it has more impact.”

— Padmaja Rai

“There have been times where I’ve said something to my boyfriend and it’s paid no heed, but when his mother says the same, it has more impact,” Padmaja Rai, a Toronto-based senior product manager, shared. “This one time, we were all having a meal together and his mom served him food like how you would for a baby — we were 29. He’s a very kind and loving guy, but he cannot take care of himself.”

This mother-son dynamic can both leave sons stunted, and encourage them to take on the behaviors they see at home. “They’re seeing their sister being relatively disadvantaged compared to them. They’re seeing their mothers being the subject of structural and everyday violence on the part of their fathers,” Singh explained. “And this is what they are socialized into believing is normal.”

For these same reasons, sons can develop a strong sense of entitlement. After all, they’re the ones who got the first glass of milk or the biggest mango or the roundest roti.

“This one time, we were all having a meal together and his mom served him food like how you would for a baby — we were 29.”

— Padmaja Rai

Some are aware of the impact of being a coddled son. “I very much was [a mama’s boy],” said Arjun Ahuja, who is London-based and works in early childhood education. “In an unhealthy way, too. I had to unlearn a lot of my patriarchal conditioning, but it sure isn’t easy when it’s so easy to benefit from it.”

Los Angeles-based Hemal Lalabhai said that his mother is his best friend. “South Asian dads are not the best husbands or fathers,” he said. “There is a responsibility as an Indian male to be more empathetic and sensitive towards the women in my life.”

Simona Giselle Fernandes, a New Jersey-based mental health counselor, is the sister of a mama’s boy. “I see how many more liberties he was given,” she shared. “I am risk-averse and a rule follower. He is very confident and open to new experiences. My wish for my South Asian sisters is that we could be raised with less fear in these dynamics, and allowed to take chances…the same way our brothers were.”

“My wish for my South Asian sisters is that we could be raised with less fear in these dynamics, and allowed to take chances…the same way our brothers were.”

— Simona Giselle Fernandes

There is a way forward, however. The more educated women are, the more they work outside the home, the less likely a family is to see the “mama’s boy” pattern, explained Ghazala Ahmed, a lecturer at Brock University. The same goes for families with higher incomes, or those living in more developed regions.

“Consider my generation,” said Ahmed. “My husband and I, we are both working, we have a good house, we are not dependent on our son. This means he and our daughter are less likely to have cultural baggage, and their children are even less likely to.”

Ahmed said she knows many mothers who have begun “training” their sons, teaching them how to do laundry and other basic tasks, in an effort to make them better prospects for marriage today. And with their sons out of the house, the chances of an unhealthy dynamic decrease.

“We need to develop men who are courteous, compassionate, and caring so that they can replace mama’s boys with men that other people would value and respect.”

— Nidhi Jose and Preeti Taneja

Then again, while Ahmed noted she sees things changing in Pakistan, Singh said mama’s boys are already a rarity in certain regions in India, such as Kerala and Tamil Nadu, which are matrilineal societies.

“[In] Kerala…there is a lot of political commitment to women’s wellbeing,” Singh added. “Many parts of India…are very safe, very healthy, very nurturing places for women to be.”

Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Bangladesh all have higher literacy rates than India as well. Sri Lanka has the highest in South Asia, with its female literacy rate one of the highest in the world. The island nation’s free education system likely helps reduce the gender gap. Sri Lanka also has a better maternal mortality ratio compared to much of South Asia, while over 80% of women make it to secondary education. According to a 2018 report, Sri Lankan women are projected to be more educated than men in the near future.

In the case of Bangladesh, “missing women” are on the decline, and the odds of female infant survival are growing closer to those of male infants, with no evidence of sex-selection. It also has one of the lowest gender gaps in political empowerment in the world, largely due to having had a female prime minister longer than any other country, with one of the highest female labour force participation rates in South Asia.

“[Change takes] a collective effort,” shared Nidhi Jose and Preeti Taneja, Toronto-based psychotherapists. “We need to develop men who are courteous, compassionate, and caring so that they can replace mama’s boys with men that other people would value and respect.”

This discourse is finally happening. It’s not just a surface-level joke anymore. This year’s satirical comedy Polite Society, depicts a British Pakistani high schooler attempting to save her older sister from marrying an obvious mama’s boy. In Never Have I Ever, although Devi and Des’s shared culture brings the two together, Des following his mother’s orders without questioning her is also a form of self-sabotage.

Raja betas or “royal sons” may be endearing themselves to their mothers in the short term, but moving forward means understanding how and why old habits came to be and what keeps them alive. Of course, it also helps to know how to wash your underwear and maybe fry an egg. Throw in a diaper change, and you’ll be as eligible as ever.

SADAF AHSAN is a culture writer based in Canada.

Comments